EPA touts success in reducing children’s chemical exposures, fails to account for emerging contaminants

By Stephen Lee | Bloomberg Environment | October 16, 2019

Read the full article by Stephen Lee (Bloomberg Environment)

“Children’s exposure to environmental hazards has been reduced dramatically in recent years, the EPA said Oct. 16.

In announcing the reduction, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler said he was frustrated that the media ‘don’t tell this side of the story.’

From 1976 to 2016, the median concentration of lead in the blood of children between ages 1 and 5 fell by 95%, according to a new Environmental Protection Agency report. Other improvements were found in air pollutants, chemicals in food, and mercury.

‘If you had similar reductions in opioid addiction or gang violence, it would lead the nightly news,’ Wheeler said at the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services annual meeting Oct. 16…

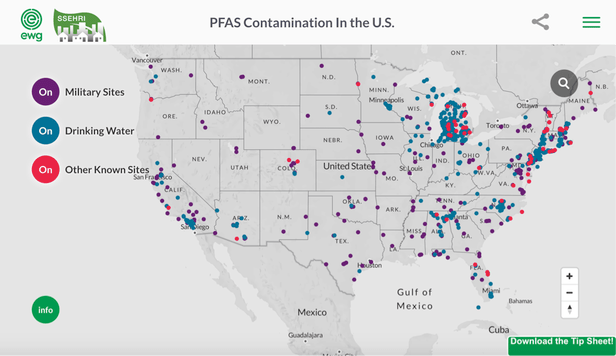

Similarly, the levels of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), also known as PFAS, fell in the blood of women of child-bearing age.

For example, PFOS levels fell 88% from 24 nanograms per milliliter in 1999 to 2000 to 3 nanograms per milliliter in 2015 to 2016. PFOA levels dropped by 80% in the same period.

Studies have found associations between prenatal exposure to PFOS or PFOA to developmental health effects, including reduced birth weight, the report said.

The report further concluded that the number of children served by community drinking water systems that failed at least some health standards dropped from 18% 1993 to 6% in 2017…

To get a fuller understanding of exposure trends, the EPA’s indicators must be updated with exposure measurements for new chemicals that replaced older ones that were phased out, said Morrissey, a toxicologist with the Washington state Department of Health.

The reductions in exposure to lead, organophosphate pesticides, certain flame retardants, and four per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) follow phaseouts of major consumer and commercial uses of these compounds years ago, Morrissey said.

Moreover, the tracking of air and drinking water contaminants is limited by the fact that, over the last 20 years, ‘it has been very hard to add a chemical to either air or water regulations,’ Morrissey said. ‘These trends don’t reflect emerging chemicals.’ ”

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: