How toxic ‘forever chemicals’ made their way into your food

By Patrick Macroy | The Hill | July 14, 2019

Read full article by Patrick Macroy (The Hill)

“It’s summertime, which means the tourists are flocking to beachside ice cream stands. With their double scoop of blueberry, however, they may be getting a dose of toxic PFAS — thanks to the lax oversight of these harmful industrial chemicals entering our food supply…

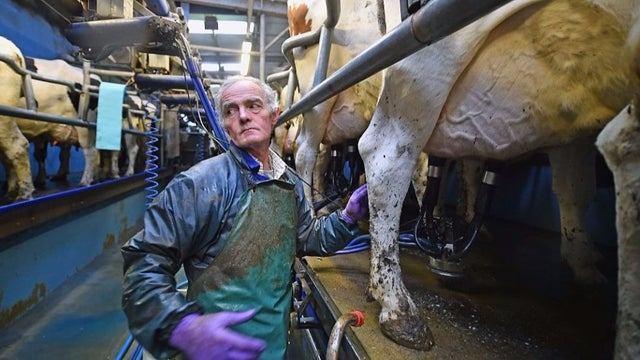

Maine became an unfortunate posterchild for PFAS contamination of dairy this spring when the story of Stoneridge Farm, where milk was found to be contaminated with a PFAS, was widely circulated in the media. National awareness of PFAS in our food has only grown, with reports of contamination of another dairy farm in New Mexico and cranberries in Massachusetts as well as chocolate cake, leafy greens and meat purchased in U.S. supermarkets.

While alarming, the stories are not surprising. Nearly every American has PFAS in their body, and scientists have long believed that the primary route of exposure for most people is through what we eat and drink.

So why are PFAS in our food?

In the case of Stoneridge Farm, cows were exposed when contaminated industrial and sewage sludge — euphemistically known as ‘biosolids’ — was used as fertilizer for their hay. The ‘beneficial’ use of such waste as a soil amendment is promoted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and all 50 states. Until the Stoneridge situation, Maine (consistent with federal rules) required sludge to be tested for heavy metals, but not PFAS. For the first time, this year, the state ordered testing for three PFAS, and nearly all sludge failed. The PFAS-laden sludge in Maine originated from areas across the state, a few relatively urban, but most rural, with minimal industrial connections.

In contrast, a New Mexico dairy also devastated by PFAS contamination has the Department of Defense to blame. The cows and their feed were watered with groundwater contaminated by PFAS firefighting foam at a nearby air force base. While the farmer was offered bottled drinking water for himself and his employees, the DoD isn’t required to provide clean water for the cows or otherwise address contamination of groundwater impacting agriculture. Recent congressional attempts to close this loophole resulted in a veto-threat from President Trump…

So, what can we do about it?

First, relevant agencies must turn off the tap and prevent PFAS from being introduced into products and into the environment in the first place.

So far, they’ve done the opposite. While fretting about cleaning up older members of the class, the EPA has continued to regularly approve the use of new PFAS sharing similar structures and the red flag of extreme persistence. Meanwhile, DoD and the Federal Aviation Administration continue to resist and slow walk efforts to phase out PFAS firefighting foam.

In contrast, states are taking the lead on preventing new PFAS contamination, with Maine and Washington starting the process to require the elimination of PFAS in food packaging, and Colorado, New York, Washington, and others eliminating or restricting PFAS in firefighting foams. Even major retailers are getting ahead of the problem, with Whole Foods eliminating PFAS from its take-out containers.

The PFAS washing down our drains and ending up in sewage sludge likely originates from many different sources. Everything from stain and water resistant fabrics, to car wash chemicals and ski waxes may contribute, in addition to food packaging and firefighting foams. Federal policy should require safer alternatives to PFAS in all products, and eliminate perverse incentives for the opposite —such as the import tariff reduction for water-resistant outerwear that encourages a near-universal application of a PFAS-based water-resistant treatment to outerwear fabrics.

Second, we must prevent another Stoneridge Farm and get serious about protecting our farm land and food from known toxic contamination. While the use of clean human or animal waste for fertilizing fields is logical and ecologically sensible, spreading sludge known to be contaminated with chemicals that don’t break down and are absorbed by plants and farm animals is not.

Until we can eliminate PFAS and prevent them from entering our sewer systems in the first place, states and municipalities must be required to test sludge and hold it to strict standards for PFAS contamination before allowing it to be applied to agricultural land. Maine initially offered a strong model for testing sludge — although in the face of intense industry pressure, the state is allowing the contaminated sludge to be spread anyway.

Finally, we need federal support to identify and clean up contaminated land and water. Congressional attention on contaminated public water supplies is obviously warranted, but the focus needs to be expanded to water intended for agricultural use and in private wells. We must identify and treat contaminated waters used in agriculture, and require that fields with a history of sludge application be systematically tested, along with the agricultural products from them…”

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: