PFAS contamination of drinking water far more prevalent than previously reported

By Sydney Evans, David Andrews, Tasha Stoiber, and Olga Naidenko | EWG | January 22, 2020

Read the full article by Sydney Evans, David Andrews, Ph.D., Tasha Stoiber, Ph.D., and Olga Naidenko, Ph.D. (EWG)

“New laboratory tests commissioned by EWG have for the first time found the toxic fluorinated chemicals known as PFAS in the drinking water of dozens of U.S. cities, including major metropolitan areas. The results confirm that the number of Americans exposed to PFAS from contaminated tap water has been dramatically underestimated by previous studies, both from the Environmental Protection Agency and EWG’s own research.

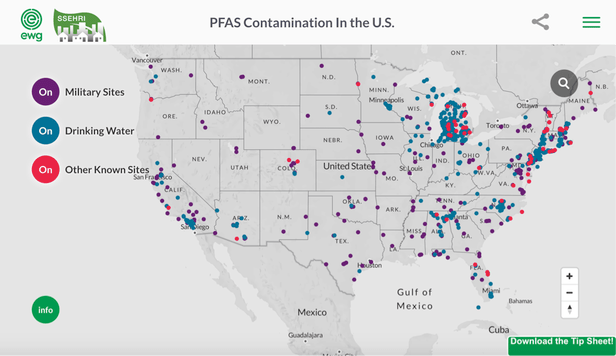

Based on our tests and new academic research that found PFAS widespread in rainwater, EWG scientists now believe PFAS is likely detectable in all major water supplies in the U.S., almost certainly in all that use surface water. EWG’s tests also found chemicals from the PFAS family that are not commonly tested for in drinking water.

Of tap water samples from 44 places in 31 states and the District of Columbia, only one location had no detectable PFAS, and only two other locations had PFAS below the level that independent studies show pose risks to human health. Some of the highest PFAS levels detected were in samples from major metropolitan areas, including Miami, Philadelphia, New Orleans and the northern New Jersey suburbs of New York City.

In 34 places where EWG’s tests found PFAS, contamination has not been publicly reported by the Environmental Protection Agency or state environmental agencies. Because PFAS are not regulated, utilities that have chosen to test independently are not required to make their results public or report them to state drinking water agencies or the EPA.

EWG’s samples – collected by staff or volunteers between May and December 2019 – were analyzed by an accredited independent laboratory for 30 different PFAS chemicals, a tiny fraction of the thousands of compounds in the family of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. An EPA-mandated sampling program that ended in 2015 tested for only a few types of PFAS and required utilities to report only detections of a higher minimal level. The EPA also only mandated testing for systems serving more than 10,000 people, whereas EWG’s project included a sample from a smaller system excluded from the EPA program. Because of those limitations, the EPA reported finding PFAS at only seven of the locations where EWG’s tests found contamination.

In the 43 samples where PFAS was detected, the total level varied from less than 1 part per trillion, or ppt, in Seattle and Tuscaloosa, Ala., to almost 186 ppt in Brunswick County, N.C. The only sample without detectable PFAS was from Meridian, Miss., which draws its drinking water from wells more than 700 feet deep.

The samples with detectable levels of PFAS contained, on average, six or seven different compounds. One sample had 13 different PFAS at varying concentrations. The list of the 30 PFAS compounds we tested for, and the frequency with which they were detected, is detailed in the appendix…

EWG’s results are in sharp contrast to nationwide sampling by most public water systems mandated by the EPA between 2013 and 2015. In the EPA tests, 36 of 43 water systems tested reported no detectable PFAS, including New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston and Washington, D.C. The EPA’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring program included only six PFAS compounds, and the minimum reporting limits were from 10 ppt to 90 ppt, obscuring the full scope of PFAS contamination…

The compounds in EWG’s study are a small fraction of the entire PFAS class of thousands of different chemicals – more than 600 are in active use – including the new generation of so-called short-chain PFAS chemicals. Chemical companies claim that short-chain PFAS are safer than the long-chain predecessors they replaced, but the EPA allowed them on the market without adequate safety testing, and the new chemicals may pose even more serious problems.

A recent study by a team of scientists at Auburn University reported that short-chain PFAS are “more widely detected, more persistent and mobile in aquatic systems, and thus may pose more risks on the human and ecosystem health” than the long-chain compounds. The researchers also noted that existing drinking water treatment approaches for the removal of long-chain PFAS are less effective for short-chain PFAS. Scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found PFAS, primarily the shorter-chain types, in all 37 rainwater samples they collected from around the country…”

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: