What’s After PFAS For Paper Food Packaging?

By Cheryl Hogue | C&EN | October 3, 2021

Read the full article by Cheryl Hogue (C&EN)

“In n the 1960s, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, the company that popularized Teflon-brand fluoropolymer coating for nonstick pans, started looking for new markets that might benefit from the strong fluorine-carbon bonds in fluorochemicals. The company began to sell stain-resistance treatments for carpets and fabrics. It also found success with fluorochemicals that help food packaging paper and paperboard resist grease and water.

For decades, scores of these per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) gained approval from regulators in the US and elsewhere. PFAS are extremely good at rendering paper wraps and containers impervious to grease and moisture oozing from hamburgers, french fries, and other foods.

Today, fast-food chains and grocery stores are realizing that fluorochemicals are not always the wonder materials they were made out to be. PFAS are environmentally persistent, and some are toxic. And studies finding that PFAS in paper wraps and boxes can migrate into food have piled up in recent years (Foods 2021, DOI: 10.3390/foods10071443).Because of those concerns, many food companies are switching from single-use containers and wraps made with PFAS to packaging without these ‘forever chemicals’ as ingredients.

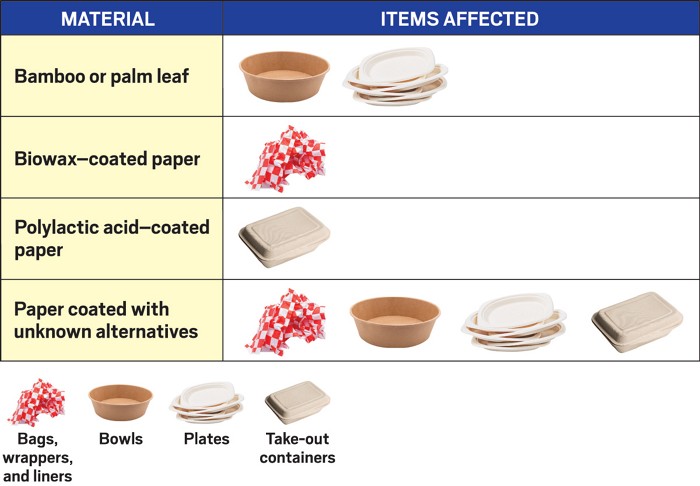

But the identities of the chemicals or coatings that companies are switching to are typically proprietary information. Citing competition, most paper and packaging companies won’t discuss the products they’re making. Supermarkets and restaurants can find third-party assurances that the paper food ware they buy has no added PFAS. Yet they don’t generally know what substances are being used instead.

‘Not only are these specific chemicals that we want removed from our packaging materials; we also want to make sure that we don’t introduce other hazardous chemicals’ as alternatives, says Boma Brown-West, director of consumer health at the Environmental Defense Fund, an advocacy group. While in an ideal world, consumers would know what the replacement chemicals are, some organizations say such knowledge might not be as important as toxicity data, reviewed confidentially by third parties, showing that they are safer than the PFAS they replace.

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the first PFAS for coating paper and paperboard, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company’s Zonyl RP, in 1967. The company called the product, which repelled water and oil, a ‘paper fluoridizer.’

For the first time ever, PFAS were on food packaging. Over time, more companies entered this market with dozens of similar chemicals. In more recent years, as the biopersistence of PFAS became clear, chemical makers shifted from long-chain PFAS—such as Zonyl RP—to short-chain ones, which generally contain six or fewer carbons, for treating food packaging materials. Many researchers believe short-chain PFAS have less potential to bioaccumulate, though their toxicity is similar to that of their longer-chain cousins.

Then in 2020, the FDA announced that four chemical manufacturers were voluntarily phasing out the sale of 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol, one of the short-chain PFAS, for use in paper and cardboard food packaging. This substance degrades in the environment to form persistent and biologically active perfluoroalkyl acids.

Today, the FDA’s Inventory of Food Contact Substances, which lists materials the agency deems “demonstrated to be safe for their intended use,” contains about 50 fluorochemicals that are approved to be marketed in the US. All the fluorochemicals in the inventory received FDA approval between 2000 and 2020.

It’s unclear how many of them are still being sold for food packaging.

PRESSURE TO SHIFT FROM PFAS

Three main forces are moving food packaging makers away from PFAS, says Shari Franjevic of Clean Production Action, a Massachusetts-based organization that promotes green chemicals, materials, and products.

One push comes from state legislation enacted in Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington that bans PFAS in food packaging, she says. Enhancing this movement is the European Union’s effort to restrict uses of all PFAS, Franjevic says.

A major US industry group is challenging efforts to phase out PFAS in products, including in food packaging.

‘All PFAS are not the same,’ stresses the American Chemistry Council, which represents chemical manufacturers, including makers of fluorochemicals. ‘It is neither scientifically accurate, nor appropriate, to group them all together by the entire class—especially when discussing the health profiles’ of these chemicals, the trade organization tells C&EN in a statement.

Members of the ACC voluntarily agreed to phase out certain PFAS for use in paper-based food packaging, the group points out. But “for many PFAS uses, there aren’t alternatives,” it says.

Bypassing the policy debate, several US environmental and health groups are urging fast-food chains and other big purchasers to voluntarily switch to PFAS-free paper wraps and containers. These efforts are a second major force in the switch away from PFAS in food packaging, Franjevic says.

‘Retailers are playing an incredibly important role in moving the marketplace away from these toxic ‘forever’ chemicals,’ says Mike Schade, campaign director of Mind the Store, in a recent statement. Mind the Store is a program run by the research and advocacy group Toxic-Free Future.“With many thousands of pounds of PFAS in circulation due to their use in food packaging, we applaud those companies that commit to phasing out these toxics in food packaging.”

As of September 2021, eight fast-food and fast-casual restaurant chains—Cava, Chipotle, Freshii, McDonald’s, Panera Bread, Sweetgreen, Taco Bell, and Wendy’s—had committed to eliminate PFAS from food packaging by dates ranging from 2020 to 2025, according to Mind the Store. The group is asking for large retailers to eliminate toxic chemicals in products and packaging.

The campaign continues to target Burger King. The CEO of that chain’s parent corporation, Restaurant Brands International, announced at a shareholders’ meeting in June that the business is exploring alternatives to PFAS.”….

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: