At Michigan schools, urgent PFAS response no guarantee

By Garret Ellison | MLive | September 5, 2019

Read full article by Garret Ellison (MLive)

“Another school year has begun and thousands of Michigan children, from preschoolers on up, have returned to a building with PFAS chemicals in the drinking water.

Although many schools are on a municipal water system with detections of the so-called ‘forever chemicals,’ dozens of schools are drawing groundwater from a well that regulators are simply testing to see how contaminant levels are fluctuating rather than requiring steps be taken to reduce or curb exposure to the toxic compounds…

Although toxicologists consider the risk from any PFAS exposure to be greater for children because their body organs are still developing, state officials aren’t pushing schools to take immediate action because only one school using well water, Robinson Elementary in Ottawa County hear Grand Haven, tested above the federal safety advisory threshold.

Ironically, that safety level may soon be eclipsed by stricter new state limits in Michigan, which currently lacks authority to force schools using well water to take any measures even if the mostly low to moderate detections are still above newly proposed limits…

‘We’re talking about children’s health,’ said Anthony Spaniola, a Troy attorney who has emerged as a leading voice for greater PFAS protections in Michigan. ‘This is not a time to be mucking around with legal niceties and gray areas.’

Some districts on well water are taking proactive steps. Others aren’t.

In Iosco County, the Whittemore-Prescott school district is using bottled water in each of its buildings even though it doesn’t have to and other districts with higher contaminant levels aren’t taking that step, which can be expensive and disruptive to operations.

In Montcalm County, the Tri-County Middle School dug a new well using state grant money even though its water showed levels below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s health advisory level of 70 parts per-trillion (ppt) for PFOS and PFOA.

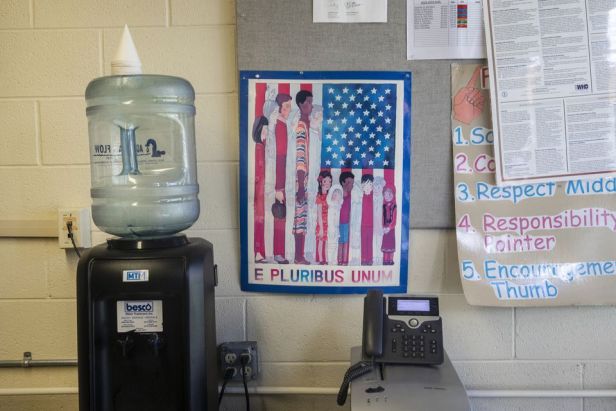

In Oakland County, administrators overseeing Glengary Elementary — where the PFAS levels tested higher than at Whittemore-Prescott — plan to connect to a municipal system next year but have only placed a bottled water dispenser near the school entrance until then.

‘The information we’ve gotten from the state, who is regulating this, is that our water remains safe for consumption,’ said William Chatfield, operations director for the Walled Lake Consolidated School District, which includes Glengary Elementary.

According to the state’s data (available for download here), the sum total of 14 different PFAS compounds tested for in Glengary’s well has ranged between 69 and 79-ppt over several tests in the past year. Of that, roughly 16 to 20-ppt is the compound PFOA — one of two compounds, along with PFOS, covered by the EPA’s non-enforceable and hotly-debated advisory level.

Published in 2016, the EPA’s 70-ppt advisory level is increasingly seen as inadequate and outdated by independent researchers and many states — including Michigan — in part, because scientific research into the health effects of PFAS is rapidly evolving, the advisory level doesn’t take human exposure studies into account and it only covers two of many PFAS compounds that tests are finding in drinking water samples.

Citing those reasons, Michigan began developing its own enforceable standards for seven PFAS compounds this year, several of which are much lower than 70-ppt and align closely with similar standards in other states. If the recommended limits on allowable PFAS levels proposed by an expert academic science panel survive the state rulemaking process intact, Michigan could have the strictest standard for the chemical PFOA of any U.S. state, at 8-ppt.

Chatfield said Glengary would comply with any rule changes…

The proposed ‘maximum contaminant levels,’ or MCLs, under consideration must yet wend through several bureaucratic steps before they would take effect. Nonetheless, regulators at EGLE are warning schools and public water systems with detections above the proposed levels to begin making plans to comply with pending changes.

The state tested about 1,380 public water systems and 460 schools, daycares and Head Start centers last year. The schools tested were those using well water, although there’s potentially PFAS in the water at any school hooked to one the 62 municipal systems with at least trace levels of PFAS detection (results here). In those cases, regulators are focusing their efforts on the water treatment plant that serves the wider community.

Ian Smith, emerging contaminants and issues coordinator for EGLE’s Drinking Water and Environmental Health Division, said schools with detections in their well ought to consider building the cost of compliance with new PFAS standards into future budget planning.

Expanded contaminant testing and new conversations between schools and health authorities ‘can kind of be taken almost as a prelude to what will happen once the MCLs will have been established,’ Smith said. Also, the state is posting data online and parents should go look that up and ‘have that conversation with their schools.’

Although there are some planning steps underway, independent experts would like to see more being done about the water that’s being consumed right now…

Anna Reade, a staff scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the proposed state standards are thresholds above which exposure could be harmful — particularly for children, who are considered at greater risk from environmental contaminants like PFAS because their immune systems, brains and other sensitive organs are still developing and children consume more water relative to body weight than adults do.

That means the same glass of water with the same PFAS concentration level results in greater exposure to a child than an adult, even though they’re drinking the same amount.

‘Ignoring these new values for a year or half-a-year is actually a significant issue for this population,’ Reade said.

‘Infants and young children are biologically very vulnerable and they’re getting higher exposures. Even though there aren’t enforceable standards yet, the fact that the science workgroup has proposed such lower values than 70 is significant.’

‘I would recommend being proactive and trying to get these daycares and schools safe water as soon as possible,’ she said. ‘The timeline on this is critical. The longer we wait, the longer we’re exposing children at this vulnerable point in their life’…

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has been drafting individualized consultations for each school with PFAS detections in its well. The process began early this year but stalled over the summer. By early April, DHHS had completed consultations for East Rockford Middle School in Kent County, EightCAP Outreach Center in Ionia County and Whittemore-Prescott schools.

No others have been finished.

Steve Crider, drinking water unit manager at DHHS, said schools are alerting parents, cooperating with EGLE testing and looking for ways to reduce PFAS exposure.

‘The risk is all being monitored,’ Crider said.

The state has letter templates on the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART) website for schools to use when notifying parents. The letters explain what PFAS are and say that it’s ‘not uncommon’ to find them in drinking water. The letters explain what the EPA’s health advisory is and say that ‘Michigan is using 70-ppt for decision making purposes.’

The templates, last revised in May, do not mention the new proposed drinking water limits, or similarly low new site risk screening levels that DHHS developed this spring.

‘We could put in language about our health-based screening levels,’ Crider said. ‘But, the end result for the students and parents is the same, which is the situation is being monitored and the schools are working to reduce the exposure to the extent practical by switching water sources if possible or using wells that are lower’ in detection.

‘But, yes — we could go update that again.’

Although some school administrators have gone further and done more research into PFAS on their own, many schools and daycares contacted by MLive said they’ve leaned heavily on the state and local health departments for guidance with responding to the detections.

The extent to which that has informed decision-making at daycares and Head Start centers in particular is somewhat unclear, as those contacted by MLive were not keen to explain what, if any, mitigation steps were being taken.

In Muskegon, 2018 testing found PFOS and PFOA at 19-ppt and Total PFAS (the sum of all detected compounds) at 40-ppt in the water at The Hop Childcare Center. Those detections increased slightly in follow-up testing this year. The daycare water serves about 60 people.

Before owner Julie Thorson hung up on a reporter, manager Melissa Griffin said the daycare was only doing quarterly testing. ‘As of right now, there is nothing we have to do because we’re at one of the lowest amounts,’ Griffin said. ‘We’re just doing what the health department tells us to do. As of right now, we don’t have to do anything’…

In Lansing, $180 million for drinking water improvements in the fiscal 2020 budget is caught up in a showdown between the governor and Republican lawmakers over road funding. More than $60 million of that is meant to install ‘hydration stations’ in all public school buildings where staff and students can fill up bottles with filtered water for drinking.

According to environmental groups following negotiations, that money has been stripped from state House and Senate versions of the budget.

‘Kids shouldn’t be drinking any of this,’ said Spaniola. ‘Nobody can prove PFAS are safe. These are contaminants. That’s why these hydrations stations are a marvelous thing. The legislature has to get their heads out of the sand and so something. But in the meantime, schools do as well.’

‘We’ve got to stop tiptoeing around this.'”

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: