How Chemours and DuPont Avoid Paying for PFAS Pollution

By David Gelles and Emily Steel | The New York Times | October 22, 2021

Read the full article by David Gelles and Emily Steel (The New York Times)

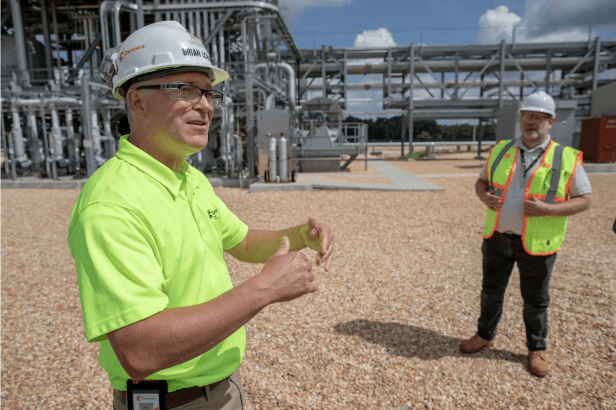

“One humid day this summer, Brian Long, a senior executive at the chemical company Chemours, took a reporter

on a tour of the Fayetteville Works factory.

Mr. Long showed off the plant’s new antipollution technologies, designed to stop a chemical called GenX from pouring into the Cape Fear

River, escaping into the air and seeping into the ground water.

There was a new high-tech filtration system. And a new thermal oxidizer, which heats waste to 2,000 degrees. And an underground wall —still under construction — to keep the chemicals out of the river. And more.

‘They’re not Band-Aids,’ Mr. Long said. ‘They’re long-term, robust solutions.’

Yet weeks later, North Carolina officials announced that Chemours had exceeded limits on how much GenX its Fayetteville factory was emitting. This month, the state fined the company $300,000 for the violations — the second time this year the company has been penalized by the state’s environmental regulator.

GenX is part of a family of chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. They allow everyday items — frying pans, rain jackets, face masks, pizza boxes — to repel water, grease and stains. Exposure to the chemicals has been linked to cancer and other serious health problems.

To avoid responsibility for what many experts believe is a public health crisis, leading chemical companies like Chemours, DuPont and 3M have deployed a potent mix of tactics.

They have used public charm offensives to persuade regulators and lawmakers to back off. They have engineered complex corporate transactions to shield themselves from legal liability. And they have rolled out a conveyor belt of scantly tested substitute chemicals that sometimes turn out to be just as dangerous as their predecessors.

‘You don’t have to live near Chemours or DuPont or 3M to have exposure to these things,’ said Linda S. Birnbaum, the former head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. ‘It is in the water. It is in our food. It’s in our homes and in our house dust. And depending where you live, it may be in our air.’

Contaminants in the Groundwater

Since 2018, potentially unsafe levels of PFAS have been found in the groundwater of more than 4,000 residential parcels near the Chemours factory in Fayetteville, N.C., according to the state’s environmental regulator. High concentrations of GenX, a type of PFAS, were found in 232 of those parcels. More than 4,000 homes qualify for under-sink treatment systems because of the contamination.

PFAS substances are known as “forever chemicals” because they do not naturally break down and can accumulate in the environment and in the blood and organs of people and animals.

When the compounds get into water supplies, the effects can be devastating. Around Madison, Wis., residents are advised not to eat the fish from nearby lakes. In Wayland, Mass., residents are drinking bottled water because the tap water is contaminated. In northern Michigan, scientists found unsafe levels of PFAS in the rain. Most Americans have been exposed to at least trace amounts of the chemicals and have them in their blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Research by chemical companies and academics has shown that exposure to PFAS has been linked to cancer, liver damage, birth defects and other health problems. GenX was supposed to be a safer alternative to earlier generations of the chemicals, but new studies are discovering similar health hazards.

This week, the Environmental Protection Agency announced that it was going to start requiring companies to test and publicly report the amount of PFAS in the products they make. It is an early step toward regulating the chemicals, though the E.P.A. has not set limits on their production or discharge.

The E.P.A. administrator, Michael S. Regan, who announced the new rules, previously was the top environmental regulator in North Carolina, where he clashed with Chemours over its GenX pollution.

‘PFAS contamination has been devastating communities for decades,’ Mr. Regan said. ‘I saw this firsthand in North Carolina.’

The situation in Fayetteville is in many ways emblematic of the battles being waged in communities nationwide. Pollution from Fayetteville Works has shown up in drinking water as far as 90 miles away from the plant.

Chemours argues that most of the pollution in North Carolina occurred long before it owned Fayetteville Works. DuPont, which built the factory in the 1960s, claims it can’t be held liable because of a corporate reorganization that took place several years ago. DuPont ‘does not produce’ the chemicals in question, ‘and we are not in a position to comment on products that are owned by other independent, publicly

traded companies,’ said a DuPont spokesman, Daniel A. Turner.

Both companies have downplayed the dangers of their chemicals and opted for occasional piecemeal fixes rather than comprehensive but costly solutions that would have protected the environment, according to interviews with scientists, lawyers, regulators, company officials and residents and a review of previously unreported documents detailing the industry’s tactics.”

This content provided by the PFAS Project.

Location:

Topics: